Four LGBTQ+ refugees share their journeys to a new start in the GTA

In Iran, my home country, homosexuality is punishable by execution. I knew I was gay from early childhood, but I only came to terms with my sexual identity at the age of 17. I’d always thought I was the only person to feel this way, and the first person I met with whom I could talk about being queer was a transgender Iranian woman. We became friends. After she ended her life by swallowing arsenic, I decided I had to do something to help other people like her.

In 2001, I began covert efforts to advance queer civil rights in Iran, but my advocacy work attracted the attention of the Islamic authorities. Fearing for my life, I fled to Turkey in 2005. But I still didn’t find safety there. One day, I was walking with my friend Amir (another gay Iranian refugee, who had been tortured and flogged in Iran), when we were suddenly chased down the street by homophobic crowds. These people beat us with the clear intent to murder us. Nobody helped us. No police came to our assistance. People just stood around watching.

Thankfully I was granted refugee status in Canada, after 13 months in Turkey. I entered the country on May 10, 2006, as a government-sponsored refugee. After living a secret life for so long, that date became my second birthday.

That nightmarish experience is seared in my memory, so I dedicated myself to speeding up the processing of other queer refugees in gay-unfriendly countries. The grassroots efforts I’d been involved with evolved into the International Railroad for Queer Refugees (IRQR), a Canadian registered charity that supports LGBTQ+ refugees, with a focus on those residing in Turkey.

Sometimes when I’m going about my life in Toronto, I see a queer refugee that I helped come to Canada. They might be holding their boyfriend or girlfriend’s hand, and they are laughing and smiling. That gives me a thrill, because I know their past struggles. It makes me super-happy to have been part of their journey to freedom.

I’m grateful to be in Canada, but my heart and my mind are with those people who are still struggling around the world. I travel three or four times a year overseas, and I’ve spent many hours listening to heartbreaking stories.

Every LGBTQ+ refugee has a unique situation—but the fear and pain they endured before coming to Canada is universal. I believe it is important that we, Canadians, know that we take a lot for granted living here. Life is not perfect in Canada, but people don’t fear for their lives, because of their sexual orientation or gender identity—unlike a lot of the refugees that I am working with. We can all do our part in welcoming LGBTQ+ refugees and ensuring they feel like they’re finally home and that they belong. Here are the stories of three queer newcomers who’ve rebuilt their lives and found some sense of hope, safety and freedom in the GTA.

Sara, Russia

As a transgender woman in Russia, Sara was harassed, ridiculed and assaulted on a near-daily basis. It’s not against the law there to be transgender, but intense anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment prevails. “Attitudes in society are such that people feel above the law in how they treat you,” Sara says. “In Russia, I had a life of pain.”

Sara only had a few close friends in her home country, and she could not openly disclose that she was trans. “It was really difficult to dress like a woman, so I always had to pretend to be someone I was not by dressing like a guy, which felt like torture for me,” she says.

As a student, Sara created an outlet for herself by making a secret second Facebook account with her female profile. She posted selfies there. But one of her classmates found the account and told everyone about it. She was cyberbullied relentlessly, and that was a breaking point.

Sara found a smuggler to make fake papers for her to come to Canada and apply for asylum in Toronto. “I’d started hormone treatments and I’d already started changing in my body and voice, so getting a visa through the regular channels would have been very difficult for me in Russia,” she explains.

About a year after landing in Toronto, Sara was accepted by the Immigration Refugee Board of Canada. The IRQR helped support her through the immigration process and get her set up in the city. Ten years on, she has a new life, a new name, a new identity and a new circle of friends. And last year, she married her soulmate.

“Here in Toronto, there are still some people who look at you strangely or call you names, because you’re trans,” says Sara. “But the number of people who support you is much, much higher.” Overall, she’s glad she uprooted her life and came to Canada. “Otherwise I couldn’t be who I am and have my husband and have a smile for the first time in a long, long time.”

Ed, Brazil

“Brazil is a place where if you have a boyfriend, you cannot hold hands on the street or be safely ‘out’—you could be punched or kicked or insulted,” says Ed. The electrical engineer never revealed that he was gay to his co-workers back home. “There would be a bad atmosphere and bad jokes, if I did,” he says.

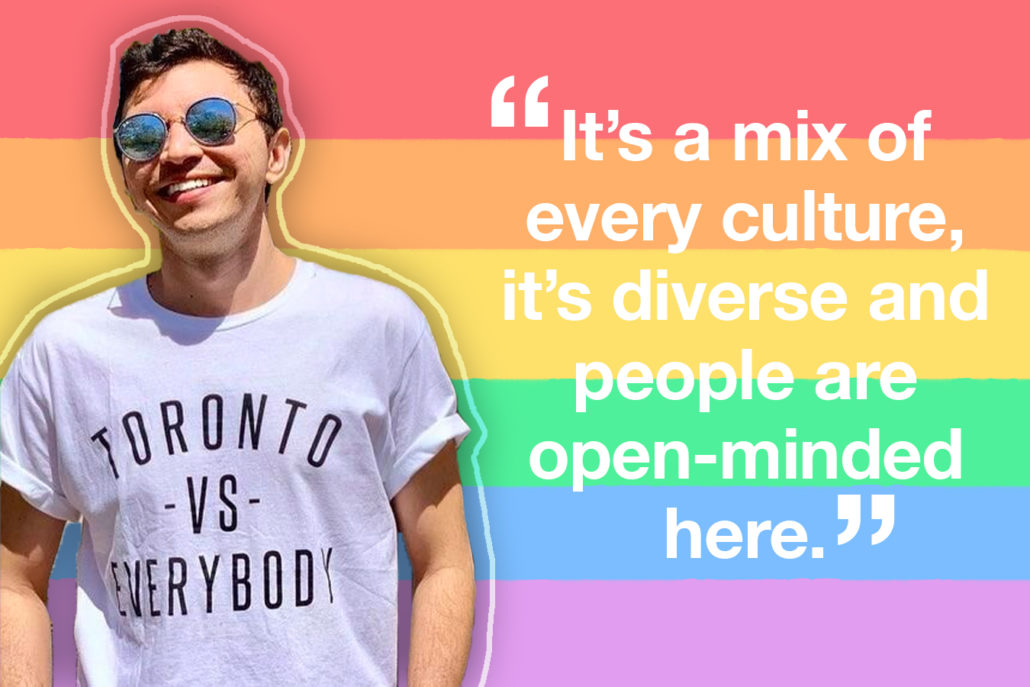

Feeling increasingly vulnerable, because of his sexual orientation, Ed sold everything he owned in Brazil and visited more than 20 countries, on short-term visas, to look for a safe haven to call home. He was initially drawn to Australia, but after two trips to Toronto, he realized this was the place for him (despite initial doubts about the winter weather). “It’s a mix of every culture, it’s diverse and people are open-minded here,” he says.

While Ed hasn’t yet applied for official refugee status, he hopes to make a permanent home for himself in Toronto. And with the recent election of extreme-right-wing and self-declared homophobe Jair Bolsonaro as president of Brazil, Ed is even more determined to apply for permanent residency here. As he saves money for university fees and works on improving his English, he has taken minimum-wage jobs such as cleaner and cashier. He says the loss of financial security and the standard of living he enjoyed in Brazil has been worth it for the freedom he has gained in Toronto.

Participating in Pride has been a highlight of Ed’s time living in the city. “Pride is not just a party here; you see families go into the streets to participate,” he says. “To see six- or seven-year-old kids learning about respect—that’s amazing.”

Ziva Gorani, Syria

Ziva, a Syrian-Kurdish pansexual trans woman, initially fled to Turkey because of the Syrian war and her vulnerability as a queer person. “Troops were targeting people like me,” she says. She worked for two years in Turkey in the humanitarian sector, becoming a spokesperson for gender equality and queer rights. But as an ‘out’ Kurdish trans woman, she experienced threats and violence.

“A friend helped me build my case with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and I was resettled in Canada within just four months, because of my sensitive situation,” Ziva says. After arriving in Toronto in October 2016, she was relieved that her life was safer. But it was initially still very hard for her as a newcomer. She had already lost her family and then the small circle of friends she’d made in Turkey. Now she was alone and disoriented as she tried to process the painful experiences she had gone through.

“That’s when I started advocating for more rights for people in a similar situation to me,” she says. “I was opening conversations to help build stronger, more inclusive resettlement services that are more sensitive to people who need to heal from traumas as they start building new lives.”

Thanks to her advocacy, Ziva was recruited to work for Moyo Health and Community Services, a non-profit agency serving the HIV/AIDS community in Mississauga, Brampton and Caledon. She also volunteers extensively in the GTA with children affected by trauma, newcomers and the LGBTQ+ community. And she’s the first trans woman to fight for feminist causes, as part of the Syrian Women’s Political Movement—a group of Syrian women politicians and activists—based within and outside of their home country—committed to gender equality and women’s empowerment.

“My mission is to open conversations about how people living with intersectional identities can access a dignified lifestyle,” Ziva says. “This freedom of speech that I have here in Canada gives me the responsibility to advocate for marginalized individuals and make others aware of the limitations these people face and the horrors they’ve been through—whether they were born outside or inside of the country.”

With files from Valerie Howes.