Howard Chandler reflects on the consequences of hate for Holocaust Remembrance Day

Howard Chandler was a young boy when the Nazis arrived in his hometown in southwestern Poland, where they first segregated the Jewish population and then deported them to labour and concentration camps. Now 89, Howard lives with his wife, Elsa (who’s also a Holocaust survivor) in North Toronto. He often speaks with school groups about his experiences and travels back to Poland on educational missions. He says it’s not easy to keep revisiting this bleak history, but as the number of people who witnessed and survived the horrors of the Holocaust dwindles, he feels compelled to keep sharing his firsthand account so that younger generations can understand the real-life consequences of hate—and the importance of actively fighting for a better world by being involved, tolerant and vigilant.

I was 11 years old and living in Wierzbnik, Poland, when the Germans first came. For me, it was an exciting time: soldiers, trucks, tanks. But a few days after they came, they burnt the synagogue down. It was September and the school year had just started. I had just graduated from third to fourth grade, and Jews were not allowed to go to school anymore. For an 11-year-old boy, that was good. My friends were mostly Christian—it was more advantageous to hang around with them than with the Jewish boys, because Jewish mothers were too protective. So, I would wait for them to finish school so we could go around and do what boys do. At first it wasn’t so bad.

But then other soldiers came and the administration changed. The Jews were separated for special treatment. Food ran out, you couldn’t buy fuel to heat the houses. In 1941, they established a ghetto and we had to share our house with three other families that were displaced. We had to share everything—the food, the medicine, our clothing. There was no privacy anymore.

We were isolated then; there were no newspapers, you couldn’t own or even listen to the radio. But we heard rumours that in other places they were rounding up the Jews and putting them on trains and taking them to farms. What we didn’t realize by then was that the Germans had erected a series of extermination camps. Instead of going to the farms as they said, they were being murdered on arrival. Who would believe they were taking civilians and killing them? Children, old people. Who would believe this?

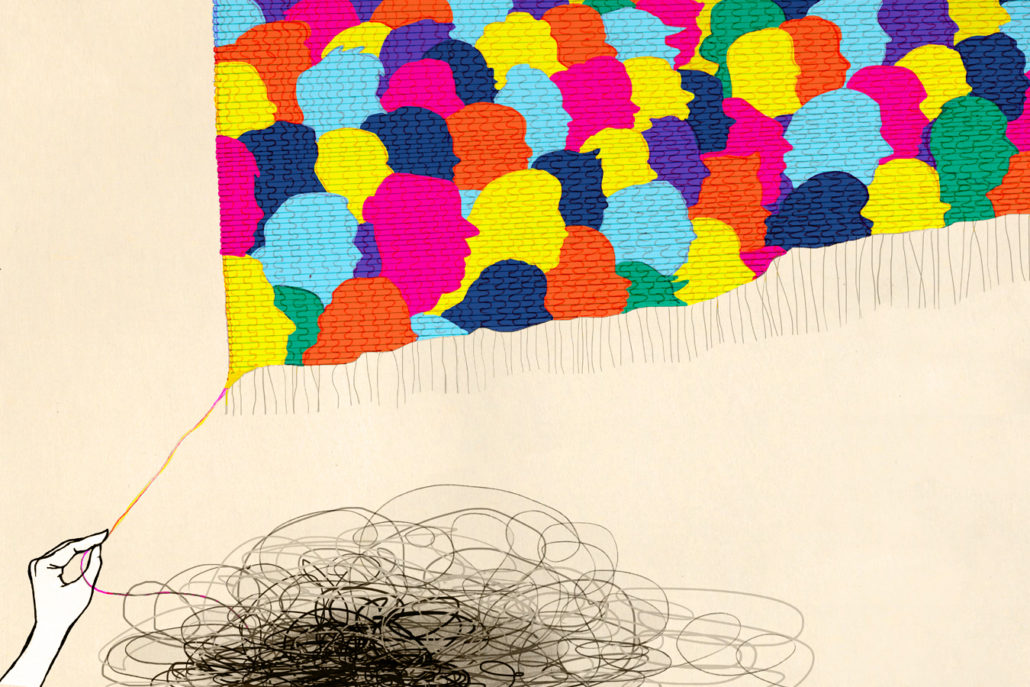

It starts with words, but where does it end up? Like they say, if you don’t learn from history, you will repeat it

But then the fatal day arrived. October 27, 1942. New soldiers came into town and surrounded the Jewish community and ordered us to assemble in the market square. Everyone came out—people who were old, people who were crippled. They shot 200 people right there. The men were separated from the women and children; those who had work permits were separated from the rest. About 4,000 people were put on a train, taken away never to be seen or heard from again. They included my mother, my sister and my younger brother. We know now that they were taken to the concentration camp Treblinka.

I followed my father; we were marched out of town to one of the labour camps they erected. And from then on, there were no Jews in Wierzbnik. There were no Jews living anywhere, except in camps.

I went back to Wierzbnik in 1987 and I’ve been back at least every second year since, both with my family and with educational groups. We have a cemetery there that we take care of—it’s the only sign that a Jewish community ever existed there. The tragedy of the Holocaust is so great that the older you get, the more it seems unbelievable. You talk to people who had similar experiences and ask each other, “Was it real? Did it really happen?” It’s so hard to believe and there are so few of us left who experienced it. But the older you get the more you realize that unless people learn what happened, it’s easily repeated.

When I meet with students they ask me, “Can this happen again?” Can it happen? It’s never stopped happening, though on a smaller scale. So, I tell them that they have to be active and involved. They have to be tolerant and they have to be vigilant. It starts with words, but where does it end up? Like they say, if you don’t learn from history, you will repeat it.