GTA parks have a problem when it comes to being accessible. Here’s how they can change for the better

Park hangs are a much-loved summer pastime. Unfortunately, not everyone can fully enjoy them. Turns out, some traditional park structures can be a challenge to navigate for people with disabilities or who use mobility aids.

But with a few thoughtful design tweaks, these urban green spaces can be upgraded to be more accessible and enjoyable for people of many abilities, says community activist Luke Anderson.

Anderson is the founder of StopGap, a charity that provides ramps to single-step storefronts, and an accessibility adviser for AllAccess, a new community initiative aimed at helping Ontario municipalities design accessible public spaces. To show how accessibility makes a difference, he guided us through the older Alexandra Park and the newly revitalized Grange Park, both in downtown Toronto, to demonstrate the challenges traditional structures create and how easy it is to change them.

Entryways

At least one ground-level entryway is a must for those who use mobility aids, Anderson says. Grange Park offers multiple entry points at ground level. The park’s Beverley Street entrances are also located by crosswalks and curb cuts—areas where the sidewalk is graded down to street level—allowing those on the opposite side of the road to mount the sidewalk easily.

“If you’re on the other side of the street trying to get to the entrance to the park, access to where you can get off the curb minimizes the amount of back-and-forth,” Anderson explains.

At Alexandra Park, on the other hand, those heading to the park from the west would need to venture out of their way a few blocks just to cross the street. Accessing parks from your point of origin, as Anderson points out, is a whole other topic of conversation. “There are so many parks that I’ve never been to just because it’s not easy to get to [them],” he says. “You have to wheel there or take a cab or Wheel-Trans, which I try to avoid.”

Seating

While Anderson doesn’t typically transfer himself from wheelchair to park bench, he appreciates having the ability to sit next to a friend. At traditional parks, many benches are placed on concrete pedestals. “Sometimes they’ll be a little bit raised up, so it doesn’t create the most equitable experience,” Anderson explains. And, benches are often located in the middle of a grassy expanse, which can be difficult for some wheelchair users to navigate. But at the updated Grange Park, many benches are located next to the paved path and sit on a spacious—and flat—concrete pad. “It’s nice to be up close, and be able to sit beside somebody that’s on a bench,” says Anderson.

Grange Park’s benches are also designed with wider seats and without an outside armrest for easy transfer when desired. During our visit, we noticed a park patron seated on a bench next to an elderly companion in a wheelchair. The pair were holding hands, which would have been more challenging with a metal armrest in the way.

Public art

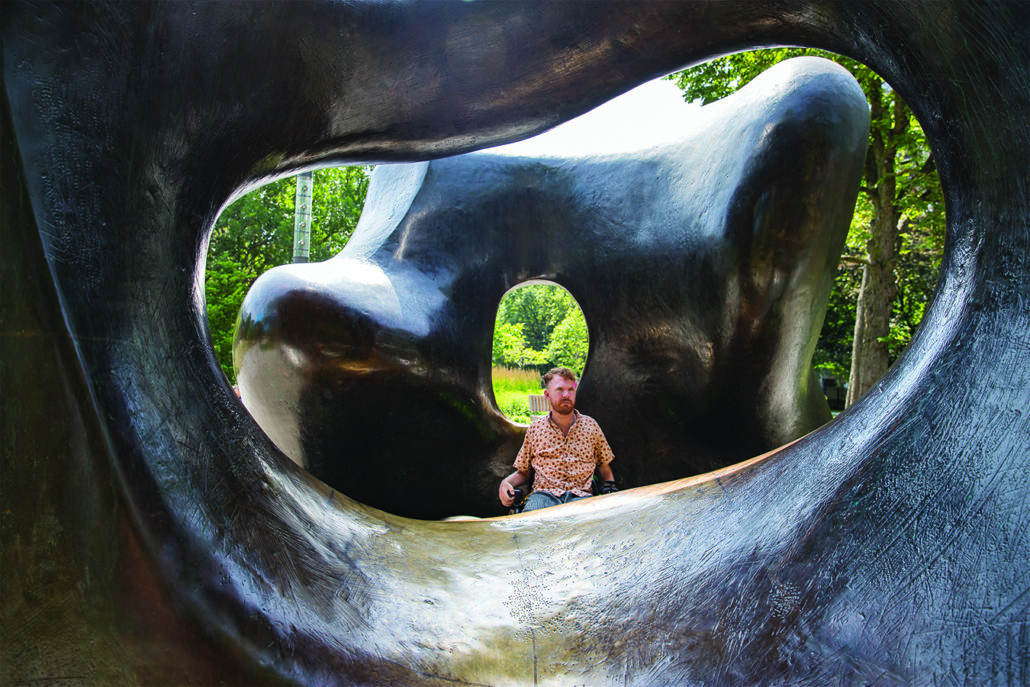

One feature that dominates the landscape of Grange Park is a large-scale Henry Moore sculpture called Large Two Forms. The piece used to live on a raised pedestal at the corner of Dundas and McCaul, but has since been relocated to Grange Park on a flat surface where park-goers—including those using mobility aids—can get up close to the piece.

Instead of being placed on a pedestal, the structure is at ground level. “It’s fun,” Anderson remarks as he wheels in between the sculpture’s two curving forms. The turn diameter of the space is just wide enough for Anderson do a full rotation—though he notes that those using scooters or larger chairs may have more difficulty.

Eating areas

“This gets me excited,” Anderson says as he approaches a picnic table at Grange Park, pointing out how the shape of the table allows him to pull up without bumping into anything. Depending on the height of the table or the way its legs are designed, Anderson is sometimes forced to awkwardly reach over to the table, or to ask others to help him eat, something that’s not exactly empowering. “Independence is invaluable,” he says.

Options for all

Anderson remains pragmatic about the design of city parks. While a park bench situated under a tree in a grassy area might not work for people who rely on mobility aids, he says that it’s okay to place seating there—it only becomes a problem if all the seating is similarly inaccessible.

“It’s all about having options,” he says. “Why deny someone else the enjoyment of sitting on a bench in a grassy area? We need to aim for having options that work for many different lived experiences.”